Case

44 Diagnosis |

Versión

en Español |

|||

Go back to clinical information and images

Diagnosis: Acute tubular damage due to hemosiderin (hemoglobinuria)

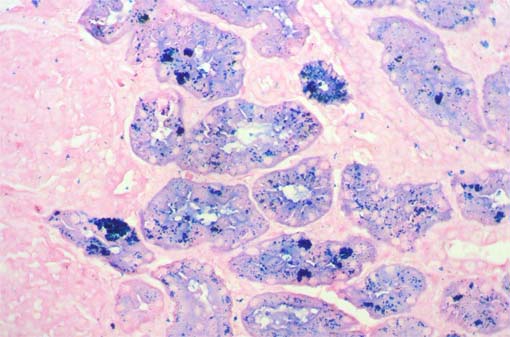

Iron staining demonstrated that the pigment was hemoglobin and its degradation product hemosiderin (see the next images):

Figure 9. Iron stain (positivity is blue), X400.

Figure 10. Iron stain, X400.

Based on the clinical evolution, and laboratory tests, the final diagnosis on this patient was Paroxismal nocurnal hemoglobinuria.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired hemolytic anemia caused by the clonal expansion of a hematopoietic progenitor cell that has acquired a mutation in the X-linked phosphatidylinositol glycan class A (PIG-A) gene. The name of the disease refers to the occurrence of hemoglobinuria, the passage of red or dark brown urine, in many patients this urine feature is evidenced in the morning. Hemoglobinuria in patients with PNH is due to intravascular lysis of red blood cells that are abnormally sensitive to complement attack. The disease is characterized by complement-mediated chronic intravascular hemolysis, resulting in hemolytic anemia and hemosiderinuria; capricious exacerbations lead to recurrent gross hemoglobinuria. Additional cardinal manifestations of PNH are a variable degree of bone marrow failure and an intrinsic propensity to thromboembolic events.The median survival has been estimated to be about 10 to 15 years. Thrombosis is the most frequent cause of death. About 10% to 15% of patients show spontaneous remission, which may occur even after many years of disease. In the past, therapy was often restricted to the treatment and prevention of complications, for example, red blood cell transfusions for the treatment of anemia, anticoagulation for the prevention of thrombosis, or immunosuppression for the treatment of bone marrow failure. Apart from bone marrow transplantation, there is currently no cure for the disease. A new targeted treatment strategy is the inhibition of the terminal complement cascade with a monoclonal antibody: eculizumab.

PIG-A is essential for the synthesis of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor molecules. PNH blood cells are therefore deficient in all proteins that use such an anchor molecule for attachment to the cell membrane. Two of these proteins regulate complement activation on the cell surface. Their deficiency therefore explains the exquisite sensitivity of PNH red blood cells to complement-mediated lysis, and this lysis is intravascular.

Most human cells, including platelets and white blood cells, express two GPI-linked inhibitors of complement activation (CD55 and CD59) as well as membrane cofactor protein (MCP or CD46), another inhibitor of complement activation that is localized at the plasma membrane via a transmembrane domain. Human red blood cells lack MCP and express only CD55 and CD59 to guard against inappropriate complement activation on their cell surface. CD55 and CD59 are GPI-linked and consequently are deficient on PNH cells. PNH red blood cells are therefore much more sensitive to lysis by complement than PNH platelets or white blood cells.

The natural history of PNH is that of a chronic disorder. The diagnosis of PNH is most frequently made in young adults; however, PNH occurs also in the elderly and in children. The disease affects both genders equally, is encountered in all parts of the world, and occurs in individuals of every socioeconomic status.

Renal Failure

in PNH

Renal vein thrombosis, acute tubulonecrosis due to pigment nephropathy,

and recurrent urinary tract infection are the major causes of renal failure

in patients with PNH. Renal vein thrombosis, in contrast to pigment nephropathy,

is associated with flank pain and macroscopic hematuria. Acute tubulonecrosis

and acute renal failure usually occur after a major hemolytic attack and

are due to hemoglobinuria and the toxicity of heme and iron, decreased

renal perfusion, and tubular obstruction with pigment casts. Siderosis

of the kidney may be found by magnetic resonance imaging in chronic (or

recurrent) cases. Progressive chronic renal failure occurs after years

of hemoglobinuria and is associated with significant glomerulonecrosis,

tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. Hemoglobinuria is also associated

with recurrent urinary tract infections, particularly in female patients

with PNH.

Diagnosis

PNH has to be suspected in patients showing mild to severe anemia with

moderate reticulocytosis, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and

possibly mild jaundice, with negative Coombs test; all these clues suggest

a non-immune hemolytic anemia. The occurrence of dark urine and urinary

hemosiderin, both evidence of intravascular hemolysis, strongly suggest

PNH. Additional signs to be considered are the presence of mild to severe

leucothrombocytopenia and/or a history of thromboembolic events of unknown

origin, including cerebrovascular accidents. In specific conditions, PNH

may be considered even in the absence of clinically evident hemolytic

anemia, such as in patients showing recurrent thromboembolic events in

the absence of documented risk factors.

At present the diagnosis of PNH is based on flow cytometry analysis of blood cells. Fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific to several GPI-APs expressed on the various blood cell lineages are available for routine testing. Molecular studies on DNA or mRNA, aimed to identify the causative specific mutation within the PIG-A gene, are clinically unnecessary (even normal individuals may harbor a few PNH cells); in fact, they do not add clinically relevant data and may be even misleading, so they are now usually limited to research purposes (Risitano AM, Rotoli B. Biologics. 2008 Jun;2(2):205-22. [PubMed link] [Free full text])

Go back to clinical information and images

Bibliography

-

Welles CC, Tambra S, Lafayette RA. Hemoglobinuria and Acute Kidney Injury Requiring Hemodialysis Following Intravenous Immunoglobulin Infusion. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Jul 21. [Epub ahead of print] [PubMed link]

-

Young NS. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and myelodysplastic syndromes: clonal expansion of PIG-A-mutant hematopoietic cells in bone marrow failure. Haematologica. 2009 Jan;94(1):3-7. [PubMed link] [Free full text]

-

Bessler M, Hiken J. The pathophysiology of disease in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:104-10. [PubMed link] [Free full text]

-

Dingli D, Luzzatto L, Pacheco JM. Neutral evolution in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 25;105(47):18496-500. [PubMed link] [Free full text]

-

Risitano AM, Rotoli B. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: pathophysiology, natural history and treatment options in the era of biological agents. Biologics. 2008 Jun;2(2):205-22. [PubMed link] [Free full text]

-

Brodsky RA. Advances in the diagnosis and therapy of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood Rev. 2008 Mar;22(2):65-74. [PubMed link] [Free full text]

-

Nair RK, Khaira A, Sharma A, Mahajan S, Dinda AK. Spectrum of renal involvement in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: report of three cases and a brief review of the literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40(2):471-5. [PubMed link]

-

Tsai CW, Wu VC, Lin WC, Huang JW, Wu MS. Acute renal failure in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Kidney Int. 2007 Jun;71(11):1187. [PubMed link]

-

Al-Harbi A, Alfurayh O, Sobh M, Akhtar M, Tashkandy MA, Shaaban A. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and renal failure. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 1998 Apr-Jun;9(2):147-51. [PubMed link] [Free full text]